Tuesday May 4th

Left home at 9.30 am

Motorway to Granada then N432 to Alcaudete then the road to Baena. Before Baena take the road to Luque but do not go into Luque take direction Dona Mencia then direction Zuheros – through Village to Castillo – same street 200 m downhill – arrived at 4.00 at Hotel Zuhayra Room 47 euros– asked for double bed

This hotel and village are certainly worth a visit (particularly if you are a walker as there are many lovely walks in the area as it is a National Park) The hotel had lovely views looking down onto olive groves.

Before investigating Zuheros took a short drive to Luque where we visited the Church which was quite spectacular for such a small town then onto the old Clock tower which since Manuel died the secret of its’ workings has not been in working order!!! Walked up and down lovely streets with houses all with tiled entrances with many pots and flowers.

Drove back to Zuheros and Visited the Museo de Costumbres Y Artes (€2)

Visiting-Zuheros-The-Museo-de-Costumbres-Y-Artes

We were given a very informative tour of this modern museum full of the old life and history of Zuheros i.e. a bedroom of the wealthy and a comparison bedroom of the poor etc – Honey Making – Bread Making – Sewing and crocheting – farming implements – olive collecting and oil manufacture – all from a period long passed.

Stopped for drinks in the square near the Church at a bar visited recently by David Beckham!

Zuheros-a-typical-street

The hotel was a little noisy as there were many walkers staying but very clean and hospitable. Had an evening meal of Clavellina (A local dish with Kidney beans and fried egg & garlic) and Mojete Zuhayra (a local dish of sliced potatoes and Boiled egg in a special sauce) this was followed by Flamenques (again a local dish of a roll of port loin with cured ham inside & breadcrumbed) After this very good meal (€28) including wine we visited the hotel bar and attempted to play a Spanish card game with some locals!! Tony also watched football on a very large screen.

Total bill for the hotel including drinks & dinner and double room €86.

Wednesday, May 5th

Had breakfast in the Hotel (included in the above price) and headed off – visited the local Co-operativo where we bought 17.5 litres of Pure Olive oil for 53 euros – this we managed to purchase in 3 large tins plus a small tin for Mum.

Leaving Zuheros took the road to Baena – Located approximately 62 km south-east of Córdoba beyond Castro del Ria is the magnificent town of Baena which has long been famous for its superb, high-quality olive oil production. The huge metal tanks for storing the oil can be seen on the outskirts of town.

The town is also well-known for its Semana Santa celebrations when rival teams of hundreds of drummers try to outdo each other with the ear-splitting sound of up to 2000 drums being struck simultaneously. Historically, Baena was important during the Moorish period, although little remains from this period, aside from a Moorish tower (formerly minaret) on the 16th-century church of Santa Maria.

Other sights include the 18th-century arcaded almacén on the Plaza de la Constitución which houses a cultural centre and one of the best tapas bars in town – Mesón Casa del Monte. For those interested in ancient olive oil production, the archaeological museum on Calle Henares is worth a visit, while the Museo de Semana Santa in the same building concentrates on the Semana Santa background and its drums. Nearby the 16th century Mudéjar convent, Madre de Dios has a fine late Gothic porch, retablo and coro with the added perk being that the nuns here sell delicious convent biscuits and magdalenas.

Places to stay include the Hotel Rincón, and the Hotel Iponuba, while most of the better restaurants and bars are centred around the attractive Plaza de la Constitución

This town is certainly worth a visit.

From Baena take N432 to Castro del Rio and Espejo

Turn left on A309 Montilla (famed for its wine of the same name. This is similar to a dry, light sherry)) but could not find a Bodega without going further into the centre of this busy town then took a cross country route through to Castillo del Almodovar del Rio (worth visiting) then on the main road into Cordoba turning off to visit the famous Moorish palace Medina Azahara just north-west of Cordoba on everybody’s itinerary.

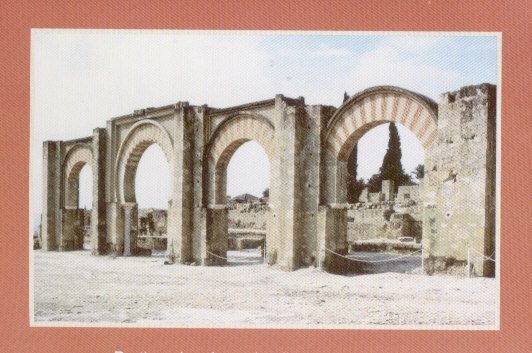

Medina Azahar – Madinat al-Zahra

We are in the year 400 of the Hegira, 1010 of our era. On the southern slopes of Jebel al-Arus, the Bride’s Mountain, the marble, jasper and precious metals of the city of Madinat al-Zahra gleam in the morning sun among silver-leafed olive groves. Bronze gryphons, lions and horses pour mountain water into thousands of marble fountains. In the shade of cypresses and palm trees and around huge reception halls, dream gardens form multi-coloured carpets, mixing myrtle and rosemary, oleanders and tuberoses, lilies and roses. From the caliph’s palace, located on the highest of the three terraces, the view extends over the whole Wadi al-Kabir valley and, in the far distance, five kilometres to the east, the large city of Cordoba can be seen.

But today the scene lacks the usual movement of thousands of civil servants who, until recently, controlled the whole of the administration of Muslim Spain. Succession in the caliphate is not clear and al-Zahra is deeply involved in the violence of a civil war. The city is occupied by rebellious troops of Berber mercenaries. Soldiers camp out in the plush reception halls. Their horses drink from the marble fountains. But they are not going to enjoy the luxuries of palace life for very long. A mob has come from nearby Cordoba and bellows at the gates of the forbidden city claiming their share of the booty. It is not long before the troops react. The first spark ignites. What the fire did not burn at the time was systematically plundered during the course of the following centuries by the Muslims themselves and then by the Christians. In the fifteenth century, Madinat al-Zahra lost even the memory of its name when it came to be called ‘Cordoba la Vieja’ (the Old Cordoba). Little by little, the ruins became buried under the mud which winters rains dragged from the mountainside. The more time passed, the more scholars developed serious doubts about the texts which spoke of its splendour, deeming them to be mere products of the imagination of their authors. When the first excavations began in 1910, only a few visible stones were left. In 936 of the Christian era, a few years after Abd al-Rahman 111 had proclaimed himself caliph, he decided to establish a prudent distance between the court and the turbulent population of the Cordobese capital. In the region west of the city where traditionally the mighty had established their country houses since Roman times, he founded a town which would eventually represent the very centre of power.

It took Abd al-Rahman twenty-five years to build Madinat al-Zahra. The city existed for merely sixty-five years. For nine centuries it slept, forgotten beneath a hard dirt cover. Following eighty years of restoration work, about one-tenth of the medina has been excavated, representing one-third of the upper terrace: the noble part which houses the alcazar with the caliph’s palace and the most important dignitaries’ houses, together with the government bodies and military buildings. On the middle terrace, only the mosque has been excavated. The souk was also at this level, together with many gardens with pools, fountains and cages housing wild animals and exotic birds. The lower terrace was devoted to infantry and cavalry housing.

To visit Madinat al-Zahra today does not mean entering an archaeological site where imagination has to make up for lack of volume. In al-Zahra, the huge amount of fragments found over many years of excavation made the experts seriously consider the question of how to present them. A museum would have meant metres and metres of display cabinets. Finally, it was decided to assemble the pieces of each palace over and then onto Cordoba

Unfortunately, it was raining and therefore this magnificent site was not at its’ best.

Some photos A brochure in the file

Continued on to Cordoba and had the usual problem finding the Hotel. Arrived at 2.00 Suggest best route is as you enter on Avenida de Medina Azahara turn right onto the Avda de la Republica Argentina carry straight on this road onto Avenida conde Vallellano – (do not be tempted to go with the traffic round to the left!!) a little further on you will see a left-hand turn to Mesquita Cathedral following signs and you come to Amador de Los Rios which takes you down the side of the Cathedral turn left into Magistral Glez which takes you up the far side of the Cathedral and park at the top in the corner where you will see Incarnation You walk up here with cases then return after to car (you can leave for 10 mins) the man from the hotel will come with you to park the car in the hotel car park! You can then leave it there for the duration as you are within walking distance of almost everything in Cordoba!

Booked by telephone only Hotel Omeyas Room €64 per night plus 12 euros for parking. Booked for two nights

A great hotel with pleasant and helpful staff at a good price. Info in the file.

Once the largest city of Roman Spain, Cordóba later formed the heart of the western Islamic empire. Today, the city is a typical bustling, noisy Andalusian city, with lots of atmosphere, fascinating sites, intriguing small streets and shops and the inevitable fabulous choice of restaurants and bars.

From the hotel on the first afternoon, we visited:-

The Mosque

British author Gerald Brenan called this impressive Arabian mosque, the third-biggest in the world with an extension of 23.000 square meters, the most beautiful and original building of all Spain.

This Mezquita initiated the so-called Califal style, which combined Roman, Gothic, Byzantine, Syrian and Persian elements and was the starting point of all Arabian-Hispanic architecture of the centuries to come, up to the Mudéjar-style of Arabians living in Spain reconquered by Christians.

Caliph Abderramán I. built the colossal hall, consisting of 11 naves with 110 columns, the capitals of which were taken from old Roman and Byzantine buildings. Above there is a second row of arcs, then an architectonic novelty, creating a unique ambience of light and shadow.

Abderramán II. added 8 more arcs in 833, with columns of white marble taken from the Roman amphitheatre of Mérida. Alhakem II built-in 961 the minaret, Mihrab, and the Kliba with its cupola of entangled arcs in 961, both being among the major attractions today. The last and most important enlargement was made in 987 by caliph Alamanzor, doubling the original size of the mosque and adding columns of blue and red marble. As the enlargement could be made only towards the West, the river Guadalquivir in the South and the palace of the caliph in the East being very close, the mosque of Cordoba is the only one that doesn’t have the Mihrab as its central point. The other particularity is that it is not orientated towards Mecca, but towards Damascus – perhaps because of nostalgic feelings of Abderramán I., who expressed in his poetry how much he was missing the mosques of his home-town.

The Mezquita dates back to the 10th century when Córdoba reached its zenith under a new emir, Abd ar-Rahman 111 who was one of the great rulers of Islamic history. At this time Córdoba was the largest, most prosperous cities of Europe, outshining Byzantium and Baghdad in science, culture and the arts. The development of the Great Mosque paralleled these new heights of splendour.

Today the Mezquita as it is known can be visited throughout the year for a €5.50 entrance fee. The approach is via the Patio de Los Naranjos, a classic Islamic ablutions courtyard which preserves both its orange trees and fountains. When the mosque was used for Moslem prayer, all nineteen naves were open to this courtyard allowing the rows of interior columns to appear like an extension of the tree with brilliant shafts of sunlight filtering through.

At first glimpse, it is immensely exciting. Jan Morris described it as “so near the desert in its tent-like forest of supporting pillars.” The architect introduced another, a horseshoe-shaped arch above the lower pillars. A second and purely aesthetic innovation was to alternate brick and stone in the arches, creating the red and white striped pattern which gives unity and distinctive character to the whole design.

The Mihram

This traditionally had two functions in Islamic worship, first it indicated the direction of Mecca (therefore prayer) and it also amplified the words of the Imam, the prayer leader. At Cordóba it is particularly magnificent. The shell-shaped ceiling is carved from a single block of marble and the chambers on either side are decorated with exquisite Byzantine mosaics of gold.

The Cathedral

In the centre of the mosque squats, a Renaissance cathedral dates back to the early sixteenth-century while, to the left is the Capilla de Villaviciosa built by Moorish craftsmen in 1371. When the Christians reconquered Cordoba in 1236, they consecrated the mosque to be the Christian cathedral. In the 13th century the first modifications were made and the Royal Chapel, Capilla Real, was added. In 1523 the Catholic Church and King Charles V. put through against the will of the town’s administration to build a Christian cathedral inside of the original mosque. Works took 234 years, so the original Gothic style is combined with Baroque and Renaissance elements. Remarkable is the Cardinal’s Chapel and its treasure, including a monstrance of Enrique de Arfe, an ivory crucifix of Alonso Cano and important sculptures and paintings.

This is just an amazing building and the best pictures are on its site and more on history etc but of course best seen in video

City Walls

The walls which used to mark the boundaries of the Jewish quarter extended virtually to the Arab walls. The latter enclose the Alcazar gardens and continue along the river bank. These stretches of wall are among the better conserved in the city’s fortified enclosure, although they are from a later period. The Roman and Arab walls crumbled and, eventually, in the 15th century after the Christian conquest, several monarchs ordered their reconstruction

city walls

The Seville Gate in Cordoba

The Gate of Seville is of considerable historical interest standing as a fortified tower from the primitive entry gate to the Alcazar or fortress. Alongside the gate rises the statue of the poet, Ibn Zaydun, the author of a treatise on love entitled ‘The Dove’s Necklace’, as well as the most modern of the many ‘Triunfos’ and columns enclosed in honour of St Raphael, the archangel who freed the city from a plague in the 13th century.

The next place we visited was The Alcazar with its beautiful gardens:-

The Palace of the Christian Kings, built-in 1328 by Alfonso XI, was a residence until the reconquest of Granada. Here was kept prisoner the Moorish caliph Boabdil. In the interior of the palace, there are remarkable Arabian baths, Roman mosaics and a sarcophagus of marble from the 3rd century. Originally there were four towers at the corners of the Alcazar, three of which can be seen still today: the Torre de Los Leones, the oldest, which forms the entrance to the palace, the octagonal Torre del Homenaje and the round Torre del Rio. The fourth tower, Torre de la Vela, was destroyed in the 19th century.

At the Eastern limit of the gardens, there are fortification walls and the Door of Seville, with a monument to the poet Ibn Hazm,

The Alcazar of the Christian Kings and its delightful gardens take up one of the river banks. The Muslim Alcazar once stood where the Episcopal Palace is today – this building was reformed in the Baroque period and was recently reconditioned in order to house the Diocesan Museum. Alongside this museum, the Exhibition Palace occupied what used to be the Church of San Jacinto and the Hospital of San Sebastian, an outstanding construction opposite the Mosque featuring a portico that stands out among the Gothic jewels in Cordoba. Inside, in the Romero de Torres hall, one can admire interesting 16th-century frescoes.

Despite originating from the Christian era, these gardens are typically Moorish in design with ponds, fountains and aromatic plants. They are open to the public after 5 pm. Adjacent to the gardens is the Royal Stables which extend to encompass the Gardens of the Campo Santo de Los Márties.

Another fantastic place – perhaps better illustrated by video

Then continuing on to

The Jewish Quarter in Cordoba

The Jewish Quarter, going back to the time of the Romans and Goths, was always an important cultural and intellectual centre. Monuments remind of the most important sons of Cordoba: Roman philosopher Séneca, Arabian philosopher Averroes and Jewish philosopher Maimonides

Here you can find also one of the few synagogues existing today in Spain, this one built-in 1315. Close to it there is the Bullfight Museum. In the Zoco you can find traditional artisans and, in summer, watch Flamenco performances. More attractions are the Chapel of San Bartolomé in Gothic-Mudejar style, the Casa del Indiano and the 11th-century minarets which today form part of Iglesia de San Juan and Convento de Santa Clara, respectively. In Calle de Comedias there are old Arabian baths.

Córdoba’s old Jewish quarter consists of a fascinating network of narrow lanes, more atmospheric and less commercialized than in Seville although souvenir shops have emerged.

At the centre of the quarter is the Synagogue in Calle de Los Judios. one of only three originals remaining in Spain. A Mudéjar construction dating from 1315. It was converted to a church in the 16th century and then held the Guild of Shoemakers until it was rediscovered in the 19th Century. The interior includes a gallery for women and plasterwork with inscriptions from Hebrew psalms and others with plant motifs on the upper part.

Its main beautifully restored wall has a semi-circular arch where a chest with the Holy Scrolls of Law used to be kept.

La Puerta de Almodovar is an entrance gate with a statue of Seneca, which together with the streets La Muralla and Averrocs form the western boundary of the Juderia. The Juderia reaches as far as Calle El Rey Heredia to the northeast and the Mosque to the south.

The Jews were established in Cordoba in Roman and Visigothic times and formed a brilliant intellectual group when Hasfay Ibn Shaprut, Abdul al Rahmm III, Jewish councillor attracted intellectuals to the court. Maimonides was born in 1135 and a statue to his honour stands in Tiberiadus Square.

This gives you a feel for the Jewish Quarter

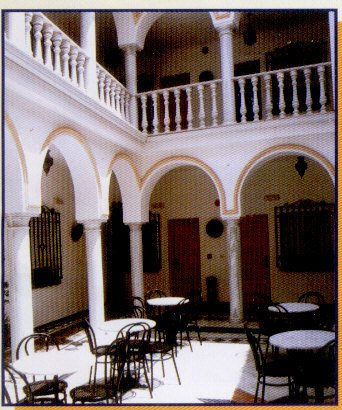

The Diocesan Museum of Fine Arts in Cordoba

This recently created museum is located at the old Episcopal Palace and is a beautiful building with a cloister of several storeys, a chapel and dining room, as well as a hall dedicated to artists from Cordoba and a gallery dedicated to mediaeval art, as well as tapestries and collections of psalm books from the Cathedral.

Visited many of the patio courtyards open to the public for this particular week in May.

In the evening visited the Restaurant Taberna Salinas C/Tundidores 3, Near Plaza Corredera (which we visited on our first trip to Cordoba) and had an excellent meal at the reasonable price of 35 euros

Thursday May 6th

The second morning started at the Calahorra Tower House at the other end of the Roman bridge

The Roman bridge in Cordoba

You can walk or drive over the bridge in either direction. It is close to the great Mosque and leads to Torre de Calahorra at the south end Some good photos on the website

There are good views of the bridge and the river from the south bank. There is usually ample parking in Avenida Fray Albino.

The Roman bridge which, according to the Arab geographer, Al-drisi ‘surpasses all other bridges in beauty and solidity’ yet reflects little of its Roman roots, owing to frequent reconstruction over many decades. In the centre of the east stone handrails, there is a little shrine to St Raphael at whose feet the devout burn candles.

It is of course unlikely that much of the original structure stands. The present structure is a medieval reconstruction though the 19th Century cobbled paving does give a roman feel. There is an irregular pattern to the 16 arches in size and abutment protections.

The Wide River Bed

The river bed is 200 m wide at this point but the water only flows through part of the width even in the winter leading to an abandoned appearance. The Cordobes do not consider the use of the river banks promenades an important tourist attraction.

Tower of La Calahorra

The Tower of La Calahorra rises up at the far end of the Roman bridge from the city centre. It was a part of the Muslim city’s defensive system built to protect the Roman bridge and the city.

It currently houses the Institute for Dialogue between Cultures. This fascinating museum is particularly educational with audiovisual presentations which vividly depict how life was lived in Cordoba during the 10th Century a unique museum uses the latest audio-visual techniques to take you on a stunning journey one thousand years back in time when half a million people lived in Europe’s largest and most magnificent city. As you ascend the three floors, absorbing the sights and sounds of Moorish Cordoba within, you can enjoy the wonderful views across the Guadalquivir to today’s city skyline, still dominated now as then by the world’s third-largest mosque.

Puerto del Puente or Bridge Gate

At the north end of the Roman bridge formerly used to enter the city enclosure near the Mosque, rises the Puerto del Puente or Bridge Gate. It was completed in the days of Philip II.

The present triumphal arch is the work of Hernán Ruiz III and replaces what was first a Roman gate mentioned at the time of Julius Cesar and later a Moorish gate. A documented restoration took place in 720 AD.

Alongside is the most ostentatious of the Triunfos erected in honour of St Raphael. It was finished by Miguel Verdiguier, a Frenchman who settled in Cordoba in the 18th century and is responsible for the distinctive Rococo style.

We then walked back over the bridge looking towards

Molino de la Albolafia The riverbed, wide enough for some garden areas and small islands inhabited by birds, was long ago used to move flour mills, of which some remains can still be seen to this day. The so-called Molino de la Albolafia which had a mill wheel which has appeared on Cordoban seals and other city emblems since the 13th century was built by the Romans. Abd al-Rahman 11 ordered a huge chain pump to be made in order to take water up to the palace gardens, but Isabella, the Catholic queen, had it taken down so as to avoid its annoying squeaking noise. What may be seen today is a reconstruction.

From here we walked to the Archaeological museum.(free entrance) Housed in a Renaissance palace, where the Roman and Moorish exhibits are attractively displayed in the inner courtyards. These include many finds from Madinat al-Zahra, the 10th century partially restored summer palace of the Caliph of Cordoba which we visited on our way into Cordoba.

Plazas are the hub of local life in Spain from the smallest village to the grandest city. Cordoba is no exception, her many plazas reflecting different historical periods. From the archaeological museum, it is a short walk through the Arco del Portillo to the delightful medieval square Plaza del Potro. (named after the colt (Potro) which adorns its fountain. And visit Meson del Potro is worth checking out for frequent excellent art and ceramic exhibitions.

Not far from this we visited Cordoba’s greatest surprise: a magnificent 17th-century three-storey arcaded Castilian-style square, Plaza de la Corredera which spectators once watched bullfights and fiestas from their covered “Boxes” surrounding the square. Our photo

We continued along the pretty tree-lined Calle San Fernando, named after Ferdinand 111, who captured Cordoba from the Moors in 1236, reaching the Town Hall on the site of a Roman Temple, several of whose impressive columns are still standing.

From here a broad avenue, named after Claudio Marcelo, the Roman Emperor who made Cordoba his Andalusian capital, leads up to the centre of nineteenth-century Cordoba, the lively Plaza Tendillas whose clock tower chimes the hours not with bells

But with a guitar – unfortunately, it was only 1.00 when we arrived in the square.

The hustle and bustle of Plaza Tendillas are in marked contrast to the tranquillity of nearby “Plaza de Los Capuchinos” with its much-venerated statue of “Cristo de Los Faroles” (Christ of the Lanterns), and the chapel of the 18th-century hospital of San Jacinto where young mothers still come to have their baby boys blessed by “our Lady of the Sorrows”, whose image is trundled through the streets every Good Friday.

Finally, we took a short walk down a steep flight of stone steps leading to “Plaza de Santa Marina” where an impressive example of one of five remaining early Gothic churches erected by the Christians who reconquered Cordoba in the 13th century faces a statue of the famous toreador, Manolete, born here in 1917 and who died in the ring at Linares in 1947. His controlled classical movements were said to reflect the sober character of his native city in contrast to the more flamboyant and impulsive Sevillian style

Whilst you are doing this walk (if it is the first week of May) have your map of the Festival de Los Patios – we did this visiting some of the patios we missed yesterday. We had lunch at Plaza Son Nicholas – on our return to the hotel we also visited Calle de las Flores – As it says ‘street of the flowers’, a painter’s and photographer’s delight. Some photos

including Tony

In the evening we had a wonderful meal at Restaurant Federacion de Penas

Friday May 7th

We left Cordoba at 10.00 am taking the Motorway NIV E5 to Sevilla –

We went to the heart of the Santa Cruz quarter. Parked in Aparcamento “Cana y Cueto” at junction of Calle Cano y Cueto and Menendez Pelayo (next to the Jardines de Murillo) From here 5 mins walk to hotel – (we took a taxi)

Booked by phone and E-Mail and have confirmation at Hotel Casa No 7 Calle Virgenes 7 Brochure in file

Room €177 euros with breakfast per night – Booked for two nights

We were disappointed in this hotel for the money. The receptionist although pleasant and booked a wonderful Flamenco show for us left for the weekend and no one was available who spoke English or Spanish to help.

The Flamenco evening was exceptional at the Centro cultural

There is so much to see we could fill this site with videos, but we won’t, just mention some places and bring in the photos we took in 2004.

According to legend, Sevilla was founded by Hercules and its origins are linked with the Tartessian civilisation. It was called Hispalis under the Romans and Isbiliya under the Moors. Its high point in its history was following the discovery of America.

Sevilla lies on the banks of the Guadalquivir and is one of the largest historical centres in Europe, it has the minaret of La Giralda, the cathedral (one of the largest in Christendom), and the Alcázar Palace. Part of its treasure includes Casa de Pilatos, the Town Hall, Archive of the Indies (where the historical records of the American continent are kept), the Fine Arts Museum (the second picture gallery in Spain) , plus convents, parish churches and palaces.

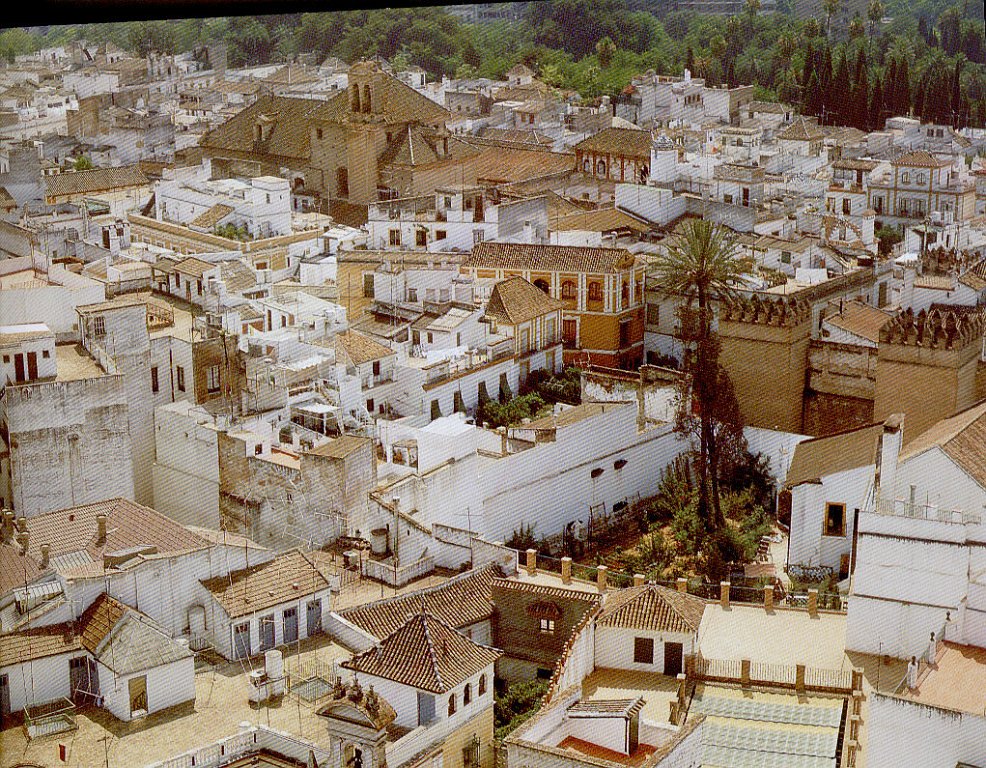

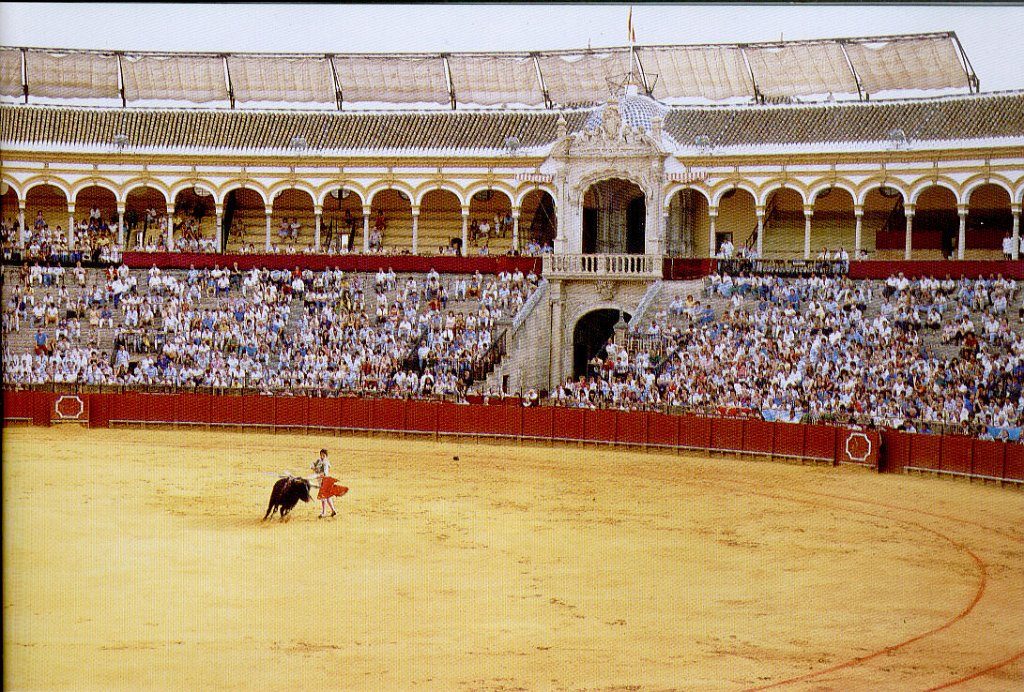

It has hosted two international exhibitions (1929 and 1992) and is the administrative capital of Andalucía. The quarter of Triana on the other side of the river, La Macarena, Santa Cruz and San Bartolomé, the street of Las Sierpes, plus La Maestranza bullring, María Luisa park and the riverside walks are all representative images of Sevilla.

For all its important monuments and fascinating history, Seville is universally famous for being a joyous town. While the Sevillians are known for their wit and sparkle, the city itself is striking for its vitality. It is the largest town in Southern Spain, the city of Carmen, Don Juan and Figaro.

The Sevillians are great actors and put on an extraordinary performance at their annual Fería de Abril, a week-long party of drink, food and dance which takes place day and night in more than a thousand especially mounted tents. But above all it allows the men to parade on their fine horses and the women to dance in brilliantly coloured gipsy dresses.

Immediately before that is Holy Week, Semana Santa, a religious festival where hooded penitents march In long processions followed by huge baroque floats on which sit Images of -the Virgin or Christ, surrounded by cheerful crowds. Both spring events are well worth experiencing.

In Seville, you will want to visit the old city, with the Cathedral and the Giralda tower at its heart. (You can climb the steps inside the tower for a magnificent view of the City) Very close by are the royal Mudéjar palace known as the Alcazar with marvellous gardens and the Santa Cruz quarter, with cramped streets, flowered balconies, richly decorated facades, hidden patios… Other sights not to be missed are, In the old city, the Casa de Pilatos, a large sixteenth-century mansion where Mudejar, Gothic and Renaissance styles blend harmoniously amidst exuberant patios and gardens and, crossing the Triana bridge over the large Guadalquívir river, the lively popular quarter of Triana with charming narrow streets around the church of Santa Ana and traditional. ceramic factories.

Seville is a city steeped in history. Throughout the narrow streets and main avenues – in fact, virtually everywhere you cast your eye, there are magnificent monuments and buildings which stand as a legacy to this city’s fascinating heritage. Many of these date from the time of the Moorish conquest (712). The cathedral was originally built as a mosque by the Almohads in the late 12th century, and later became the largest Gothic church in the world.

One of the richest areas of the city, in terms of the sheer number of monuments, is the Barrio Santa Cruz which is very much in character with Seville’s romantic image, its streets narrow and torturous to keep out the sun, with houses brilliantly whitewashed and barricaded with iron grilles behind which girls once kept chaste evening rendezvous with their novios. Almost all the houses have patios, often surprisingly large and in summer these become the principal family living room.

Near here is the Plaza de España, designed as the centrepiece of the Spanish Americas fair, and on the edge of the beautiful Maria Luisa Park

On a much smaller scale are the tranquil gardens of the Casa de Pilatos which, despite being built well after the Moslem period, demonstrates how long the interest in Mudejar architecture continued.

Museums are, not surprising, well represented in Seville, including the spectacular Museo de Bellas Artes which is a treasure house in this city of artists where such masters as Velazquez have founded whole styles of art that have been very influential in the world of painting.

Giralda

The Giralda is one of the most magnificent buildings in Sevilla and dominates the skyline. You can ascend to the bell chamber for a remarkable view of the city, and equally remarkable, a glimpse of the Gothic details of the cathedral’s buttresses and statuary. The most impressive of all is the tower’s inner construction, a series of 35 gently inclining ramps wide enough to allow the passage of two mounted guards.

The Moorish structure took twelve years to construct and derives its firm, simply beauty from the shadows formed by blocks of brick trellis work, different on each side, and relieved by a succession of arched niches and windows. The original harmony has been somewhat spoiled by the Renaissance addition of balconies and, to a great extent, by the four diminishing storeys of the belfry added in the mid-sixteenth century, following the demolition by an earthquake of the original copper sphere.

Alcazar

It’s easy to be fooled into thinking this is a Moorish palace, some of the rooms and courtyards seem to come straight from the Alhambra. Most of them were actually built – by Moorish workmen it’s true – for King Pedro the Cruel of Castile in the 1360s. who, with his mistress, Maria de Padilla, lived in and ruled from the Alcazar. Pedro embarked upon a complete rebuilding of the palace, employing workmen from Granada and utilising fragments of earlier Moorish buildings in Seville, Cordoba and Valencia.

Pedro’s work forms the nucleus of the Alcazar as it is today and, despite numerous restorations necessitated by fires and earth tremors, it offers some of the best surviving examples of Mudejar architecture.

Later monarchs, however, have left all too many traces and additions – the most mundane of which is probably the kitchens constructed for General Franco who stayed in the royal apartments whenever he visited Seville.

Cathedral

Seville’s cathedral occupies the site of a great mosque in the late 12th century. Later, Christian architects added the extra dimension of height. Its central nave rises to an awesome 42 metres and even the side chapels seem tall enough to contain an ordinary church. The total area covers 11,520 square metres and new calculations, based on cubic measurements, have now pushed it in front of Saint Paul’s in London and Saint Peter’s in Rome, as the largest church in the world.

Sheer size and grandeur are, inevitably, the chief characteristics of the cathedral, but as you grow used to the gloom, two other qualities stand out with equal force – the rhythmic balance and interplay between the parts and an impressive overall simplicity and restraint in decoration. All successive ages have left monuments of their own wealth and style, but these have been restricted to the two rows of side chapels. In the main body of the cathedral, only the great box-like structure of the core stands out, filling the central portion of the nave.

This opens onto the Capilla Mayor, dominated by a vast Gothic retablo comprised of 45 carved scenes from the life of Christ. The lifetime’s work of a single craftsman, Pierre Dancart, this is the ultimate masterpiece of the cathedral – the largest and richest altarpiece in the world and one of the finest examples of Gothic woodcarving anywhere. The guides provide staggering statistics on the amount of gold involved.

At the end of the first aisle are a series of rooms designed in the rich Plateresque style in 1530 by Diego de Riano, one of the foremost exponents of this predominantly decorative architecture of the late Spanish Renaissance. Through the antechamber, you reach the Capitular with its magnificent domed ceiling mirrored in the marble decoration of the floor. There are a number of paintings by Murillo here, the finest of which, a flowing Conception occupies the place of honour.

Alongside this room is the grandiose Sacrista mayor which houses the treasury. Amid a confusing collection of silver reliquaries and monstrances are the keys presented to Fernando by the Moorish and Jewish communities on the surrender of the city, sculpted into the latter in stylised Arabic script are the words ‘May Allah render eternal the dominion of Islam in the city.’

The tomb of Christopher Columbus is always of great interest to scholars and tourists alike.

The climb to the top of Giralda is considered well worth the effort for the views alone.

Patio de los Naranjos

Located just outside the Cathedral, the Patio de Los Naranjos dates back to Moorish times when worshippers would wash their hands and feet in the fountain here – under the orange trees – before their daily prayers.

The Barrio Santa Cruz

This is an enchanting part of the city: a honeycomb of narrow cobbled streets, pavement cafes/bars and plazas flanked by orange trees. It is part of the old Jewish quarter. Many of the best-known sights are grouped here, the cavernous Gothic cathedral with its landmark Giralda, the splendid Reales Alcazares with the royal palaces and lush gardens of Pedro 1 and Carlos V, and the Archivo de Indias, whose documents tell of Spain’s exploration and conquest of the New World.

Spreading northeast from these great monuments is an enchanting maze of whitewashed streets. The artist Bartolome Esteban Murillo lived here in the 17th century while his contemporary, Juan de Valdes Leal, decorated the Hospital de Los Venerables, one of the most beautiful buildings is the Baroque Hospicio de Los Venerables Sacerdotes near the centre in a plaza of the same name.

Further north, busy Calle de las Sierpes, is one of Seville’s favourite shopping streets. Its adjacent market squares, such as the delightful Plaza del Salvador, provided backdrops for Cervantes’ stories. Nearby the ornate facades and interiors of the Ayuntamiento and the Casa de Pilatos, a gem of Andalusian architecture, testify to the great wealth and artistry that flowed into the city in the 16th century. At the southern end of the Barrio are the formal gardens ‘Jardines de Murillo’ which were once orchards and vegetable plots in the grounds of the Reales Alcazares.

The Plaza de España

Laid out in 1929 for an abortive ‘Fair of the Americas’, the Plaza de España and adjoining Maria Luisa Park are among the most pleasant – and impressive – public spaces in Spain. They are an ideal place to spend the middle part of the day, just a ten-minute walk to the east of the cathedral.

Today, the plaza mainly comprises government offices while the surrounding moat can be best appreciated by renting out a rowing boat. A vast semicircular complex with fountains, monumental staircases and a mass of tile work, it is quite spectacular.

There is a tiled alcove named after each of the provinces of Spain. Patriots like to have their photos taken in their home province.

The Maria Luisa Park in Seville

For all its old fashioned grace, Seville has been one of the most forward-looking and progressive cities in Spain during this century. In the 1920s, while they were redirecting the Guadalquivir and building the new port and factories that are the foundation of the city’s growth today, the Sevillanos decided to put on an exposition. In a tremendous burst of energy, they turned the entire southern end of the city into an expanse of gardens and grand boulevards. The centre of it is Parque de Maria Luisa, a paradisical half-mile of palms and orange trees, elms and Mediterranean pines, covered with flower beds and dotted with hidden bowers, ponds and pavilions. Now that the trees and shrubs have reached maturity, the genius of the landscapers can be appreciated – this is one of the loveliest parks in Europe.

The park is designed like the Plaza de España in a mix of 1920s Art Deco and mock Mudejar by the architect, Anibal Gonzalez. Scattered about and round the edge are more buildings from 1929 fair, some of them surprisingly opulent, built in the last months before the Wall Street crash undercut the scheme’s impetus – a good example is the stylish Guatemala building, off the Paseo de la Palmera.

Towards the end of the park, the grandest mansions from the fair have been adapted as museums. The farthest contains the city’s archaeology collections. The main exhibits are Roman mosaics and artefacts from nearby Italica, along with a unique Phoenician statuette of Astarte-Tanit, the virgin goddess once worshipped throughout the Mediterranean.

Nearby is the Royal Tobacco Factory, forever associated with the fictional gipsy heroine, Carmen, who toiled in its sultry halls. Today it is part of the university.

The Casa de Pilatos

The first Marquis of Tarifa departed on a Grand Tour of Europe and the Holy Land in 1518. Two years later he returned, enraptured by the architectural and decorative wonders of High Renaissance Italy. he spent the rest of his life fashioning a new aesthetic, which was very influential. His palace in Seville was called the House of Pilate because it was thought to resemble Pontius Pilate’s home in Jerusalem and later became a luxurious showcase for the new style.

Subsequent owners have contributed to the building over time and it is currently the residence of the Dukes of Medinaceli and still one of the finest palaces in Seville. The marble portal was commissioned by the Marquis in 1529 by Genoan craftsmen, while the courtyard is typically Mudejar in style and decoration with tiles work and intricate plasterwork. This is surrounded by irregularly spaced arches capped with delicate Gothic balustrades. In the corners are three Roman statues, depicting Minerva, a dancing muse and Ceres, and a fourth statue, a Greek original of Athena, dating from the 5th century BC.

Towards the end of the park, the grandest mansions from the fair have been adapted as museums. The farthest contains the city’s archaeology collections. The main exhibits are Roman mosaics and artefacts from nearby Italica, along with a unique Phoenician statuette of Astarte-Tanit, the virgin goddess once worshipped throughout the Mediterranean.

Nearby is the Royal Tobacco Factory, forever associated with the fictional gipsy heroine, Carmen, who toiled in its sultry halls. Today it is part of the university

Once a convent, this magnificent art museum has been lovingly restored and is now one of the finest in Spain. Located in a tiny plaza away from the city centre bustle, the building dates back to 1612, the work of architect, Juan de Oviedo.

It is built around three patios which are decorated with flowers, trees and the distinctive Seville tile work. The museum’s impressive collection of Spanish art and sculpture extends from the medieval to the modern, focusing on the work of Seville School artists, such as Bartolome, Esteban Murillo, Juan de Vales Leal and Francisco de Zurbaran. The Italian sculptor Torregiani (the fellow who broke Michelangelo’s nose and died in a Seville prison), left an uncanny barbaric wooden St Jerome

Paseo de Cristobal Colon (Christopher Columbus Parade)

Back in Columbus’ time, the river here would be crowded with boats, nowadays the occasional tourist steamer chugs by or pedal boat.

But it is still the most charming paseo which during the weekends is thronged with strolling lovers and Spanish families dressed in their Sunday best. The view across the river is quite beautiful with a row of typical Andaluz houses with wrought-iron balconies, several of which have been converted into thriving restaurants

Restaurants here are more expensive than most in Spain, but even around the cathedral and the Barrio Santa Cruz, there are few places that can simply be dismissed as tourist traps. Remember that in the evening the ‘Sevillanos’, even more than most Andalusians, enjoy bar-hopping for tapas, rather than sitting down for one meal; two Sevillanos in a bar is a party, three is a fiesta!

Seville’s cheapest restaurants are located around Calle San Eloy. Particularly recommended are the moriscos bars in the small streets of Calle Tetuan and Calle Sierpes. The Antigua Bodequita is a find, a tiny bar opposite the church on Plaza del Salvador, but if you just fancy cakes, coffee or ice cream head for La Campana on Calle Sierpes. Established in 1885, it’s undoubtedly one of the quaintest cafes in the city.

Saturday, May 8th Sevilla

Breakfast was served by a Russian in white gloves – and although a good meal was very light on cutlery and plates.

Wandered around the city – looking at the shops and enjoying the fact that we were in a young vibrant city and very Spanish –

Visited the Cathedral

Map of Seville in the file.

Sunday, May 9th

Return A92 Motorway to Granada and then home. Motorway all the way. Nearly 700 kms and took 7 hours

Our photos of our trip to Seville

Seville Cathedral 3rd largest in Christian World

A lovely building on our walk

Sevilla city garden

The Barrio de Santa Cruz Sevilla

Hat shop in Sevilla

Calle Betis on the banks of the Guadalquivir

Real Plaza de la Maestranza

Patio de las Doncellas

La Barqueta Bridge

Wedding Photography on the banks of the River Guadalquivir

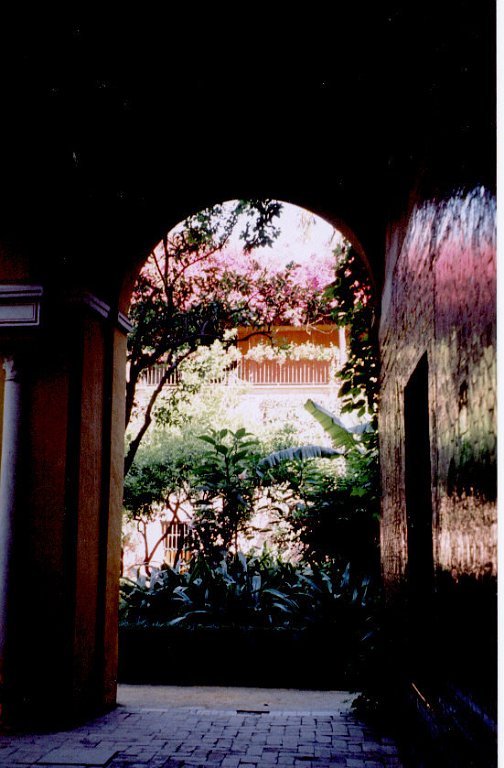

Typical courtyard in the Barrio

The Giralda